Writing for Meaning and Understanding: The Power of Integrated ELA and Social Studies

NOTE: There is no recording for this webinar.

Writing for Meaning and Understanding: The Power of Integrated ELA and Social Studies

Strong writing instruction depends on explicit teaching, purposeful practice, and meaningful content. When ELA and social studies are intentionally integrated, writing becomes a powerful tool for building knowledge, deepening comprehension, and helping students make sense of the world.

Key Takeaways

Writing for Meaning and Understanding: The Power of Integrated ELA and Social Studies

When ELA and social studies are intentionally integrated, writing instruction brings together the best of both worlds: explicit teaching of writing skills and meaningful content that gives those skills purpose. Students still learn how sentences work, how ideas are organized, and how genre shapes writing. But they learn those skills while writing about real ideas, real texts, and real questions about the world.

In an integrated approach, writing becomes more than practice. It becomes a tool for thinking, for building knowledge, and for making sense of ideas that stretch across texts, discussions, and disciplines. Rather than asking educators to choose between strong writing instruction and meaningful content, integration makes it possible to do both well, at the same time.

What follows is a closer look at what high-quality writing instruction requires, why integration strengthens it, and how this approach plays out across a single integrated ELA and social studies module.

What strong writing instruction requires

Across research, curriculum reviews, and classroom experience, there is growing agreement about what helps students become stronger writers. Writing improves when it is taught explicitly, practiced daily, and grounded in purpose and knowledge (Graham et al., 2012; Graham et al., 2018).

Writing is taught, not assumed

Writing instruction must be explicit. Students need instruction in sentence construction, paragraph structure, and genre expectations. It should start with the smallest units of meaning and build intentionally over time. Sentence-level work is not separate from real writing. It is what allows students to write with clarity and confidence (de Jong et al., 2015; Graham et al., 2012).

Writing should not be a mystery. It's not something students are expected to pick up naturally or suddenly produce during a summative assessment. Strong writing is built on purpose, starting with words, then sentences, then paragraphs, and practiced every day. Connie Hebert, Director of Curriculum, ELA, inquirED

When students are expected to write full responses without being taught how sentences and paragraphs work, the result is frustration rather than growth. Writing improves when teachers slow down and teach the building blocks directly (Graham et al., 2012; Graham & Harris, 2003).

Writing is a process driven by purpose

Writing must be purposeful. Students write differently when they know why they are writing and who they are writing for. Strong instruction helps students understand whether they are explaining, informing, narrating, or persuading, and what each purpose requires of them as writers (Graham & Perin, 2007; Graham et al., 2018).

That purpose is what gives the writing process meaning. Students plan by selecting ideas that serve their purpose. They rehearse by talking through what they want their reader to understand. They draft with attention to clarity, not just completion. They revise to strengthen ideas and organization, and they edit so conventions support, rather than distract from, meaning (Graham et al., 2018).

When students learn writing as a purposeful process, it becomes less mysterious and more manageable. Each step exists for a reason, and students can see how those steps help them communicate more clearly.

Writing depends on knowledge

Writing must be grounded in knowledge. Students write best when they are working with ideas they have encountered through reading, discussion, and investigation. When writing tasks are disconnected from meaningful content, students often rely on vague language and surface-level thinking. When asked to explain ideas they do not yet understand, writing becomes an exercise in filling space rather than communicating meaning (Hochman & Wexler, 2019).

{{download}}

Prior content knowledge changes what students are able to do as writers. Ideas come more readily because students are not starting from a knowledge deficit. Students have the vocabulary to be precise, the concepts to organize their thinking, and the mental models to explain relationships between ideas. Writing about texts and ideas strengthens comprehension, and deeper comprehension, in turn, supports stronger writing (Graham & Hebert, 2011; Graham et al., 2020).

The “yes, and” of writing and integration

Strong writing instruction matters on its own. Explicit sentence-level work, clear genre expectations, and a visible writing process are essential. But when writing instruction within a core ELA program is intentionally integrated with a core social studies program, it becomes even more powerful (Graham et al., 2020).

This is not an either-or decision. Integration is not about sacrificing writing instruction in order to cover content. When done well, it is a yes-and approach that strengthens both writing development and content understanding.

Integration works because it aligns what students are learning to write with what they are learning about the world.

Writing for disciplinary understanding

When students write in the context of social studies, writing becomes a tool for thinking.

As students engage in daily, explicit writing instruction, they do so in the context of meaningful investigations. As they develop writing mechanics through a scaffolded progression, social studies content gives them something real to think about and explain. Writing becomes a way to make sense of history, civics, geography, and economics, supporting both comprehension and disciplinary learning (Graham et al., 2020).

Rather than practicing writing skills in isolation, students use writing to explain how communities function, how people solve problems, and how shared efforts lead to change. Writing instruction remains explicit, but its purpose becomes clearer and more compelling.

Why integration strengthens writing instruction

Integrated instruction creates the conditions that strong writing instruction depends on.

First, it builds knowledge systematically. Social studies provides coherent content that grows across texts and lessons, giving students the vocabulary, concepts, and background knowledge they need to write with clarity and precision (Hochman & Wexler, 2019).

Second, it creates authentic reasons to write. Students are not responding to disconnected prompts. They are writing to explain ideas that matter, using evidence from texts, images, and discussions to support their thinking (Graham et al., 2020).

Third, it supports transfer. When students learn to write about real ideas across multiple contexts, they are more likely to apply writing strategies independently. Writing becomes a way of thinking across disciplines, not just an ELA task (Graham et al., 2020).

This is where integration moves from a structural choice to an instructional advantage.

What writing looks like across an integrated ELA and social studies module

To see why integration strengthens writing instruction, it helps to zoom out and look at how writing develops across a full instructional arc, not just in a single lesson.

In an early grade integrated ELA and social studies module focused on civic cooperation, students spend 10–12 lessons reading, discussing, and writing about how people work together to achieve shared goals. Across the module, students move from familiar contexts to more complex historical examples, while writing instruction remains explicit, scaffolded, and purposeful throughout.

The core texts anchor the knowledge-building sequence:

- In Our Garden (realistic fiction)

- The Power of Cooperation (informational text with photographs and infographics)

- Building the Statue of Liberty (informational text with timelines and visual sources)

- Let Liberty Rise! (narrative nonfiction)

Rather than treating writing as something that happens at the end, writing is woven through every phase of the investigation. Sentence-level work, paragraph structure, and the writing process are taught alongside content, so students are always writing to explain something they are actively learning.

Starting with a familiar context: writing about a school community

The module begins with In Our Garden, a story about Millie and her classmates working together to build a rooftop school garden.

In these early lessons, writing focuses on building strong sentences while students develop a shared understanding of cooperation. Students identify the characters, setting, problem, and solution, then expand simple sentences by adding where and why details. Writing is grounded in the text and closely connected to discussion, helping students explain why Millie could not solve the problem alone and how the community worked together.

As students write about the garden, they are not just practicing mechanics. They are learning to explain how cooperation strengthens a school community. Writing helps them name actions, connect cause and effect, and articulate ideas that matter.

Expanding the lens: writing about a city community

Next, students turn to The Power of Cooperation, an informational text that shows how New Yorkers transformed abandoned railroad tracks into the High Line.

Here, the content becomes less familiar and more abstract, and the writing instruction adjusts to meet that shift. Students analyze photographs, infographics, and text features to identify how people contributed in different ways. Writing instruction emphasizes paragraph structure, helping students identify a topic sentence, select important details, and craft an ending sentence that reinforces the main idea.

Students build an informational paragraph explaining how cooperation allowed a community to accomplish something no individual could do alone. Writing remains scaffolded and explicit, but now students are synthesizing information from multiple sources and learning how evidence supports explanation.

Extending understanding across history: writing about national cooperation

The final sequence focuses on national and international cooperation through Building the Statue of Liberty and Let Liberty Rise!

Students study timelines, videos, and historical images to understand how people in France and the United States contributed money, ideas, labor, and effort to build the Statue of Liberty. Writing instruction now spans the full writing process. Students plan, orally rehearse, draft, revise, edit, and publish an informational paragraph explaining how cooperation made the statue possible.

At this point in the module, students are doing far more than filling in a paragraph frame. They are using writing to organize historical information, explain relationships between ideas, and communicate what they have learned about how communities work toward shared goals.

Why this arc matters

Across these 10–12 lessons, the content grows more complex, but the writing instruction never disappears. Instead, it becomes more purposeful.

Students move from writing about a school garden, to a city park, to a national monument. Each step builds knowledge, vocabulary, and conceptual understanding. Writing serves as both a practice ground for sentence and paragraph skills and a tool for making sense of increasingly complex social studies ideas.

This is the power of integrated ELA and social studies. Writing instruction stays explicit and structured, while the content gives students something real to think about and explain. Writing becomes a way students learn, not just a way they show learning at the end.

What this means for classrooms

Teachers are often asked to choose between depth and coverage, skills and content, writing instruction and social studies.

They should not have to.

When writing instruction is explicit and grounded in meaningful content, students develop the skills they need to communicate clearly and the understanding they need to say something worth communicating. Integration does not replace strong writing instruction. It gives it a reason to exist.

A final note

This view of writing as both a skill and a tool for understanding is a big reason inquirED designed Inkwell the way we did. Inkwell brings ELA and social studies together in a single, fully integrated daily block, so writing instruction remains explicit while students are consistently building knowledge. As students read, write, speak, and listen, they are learning how sentences and paragraphs work, while also using writing to make sense of how communities function, how people cooperate to solve problems, and how history and civics shape the world around them.

For teachers, this means working within one coherent instructional structure aligned to both ELA and social studies standards, rather than juggling separate programs or disconnected pacing guides. For students, it means consistent routines, connected content, and daily writing grounded in meaningful texts that support both skill development and comprehension.

If you would like to see how this integrated approach supports strong writing instruction in practice, or explore sample lessons and modules, you can learn more about Inkwell here.

References

de Jong, P. F., Koster, M., Tribushinina, E., & van den Bergh, H. (2015). Teaching children to write: A meta-analysis of writing intervention research. Journal of Writing Research, 7(2), 249–274.

Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (2003). Students with learning disabilities and the process of writing. Handbook of learning disabilities, 323–344.

Graham, S., & Hebert, M. (2010). Writing to read: Evidence for how writing can improve reading. Alliance for Excellent Education.

Graham, S., & Hebert, M. (2011). Writing to read: A meta-analysis of the impact of writing and writing instruction on reading. Harvard Educational Review, 81(4), 710–744.

Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents. Scientific Studies of Reading, 11(1), 3–20.

Graham, S., Kiuhara, S. A., & MacKay, M. (2020). The effects of writing on learning in science, social studies, and mathematics. Review of Educational Research, 90(2), 179–226.

Graham, S., McKeown, D., Kiuhara, S., & Harris, K. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for students in the elementary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 879–896.

Graham, S., et al. (2018). Teaching elementary school students to be effective writers: A practice guide. Institute of Education Sciences.

Hochman, J. C., & Wexler, N. (2019). The connections between writing, knowledge acquisition, and reading comprehension. Perspectives on Language and Literacy, 45(2), 10–15.

Resources

Keep reading

See more of this series

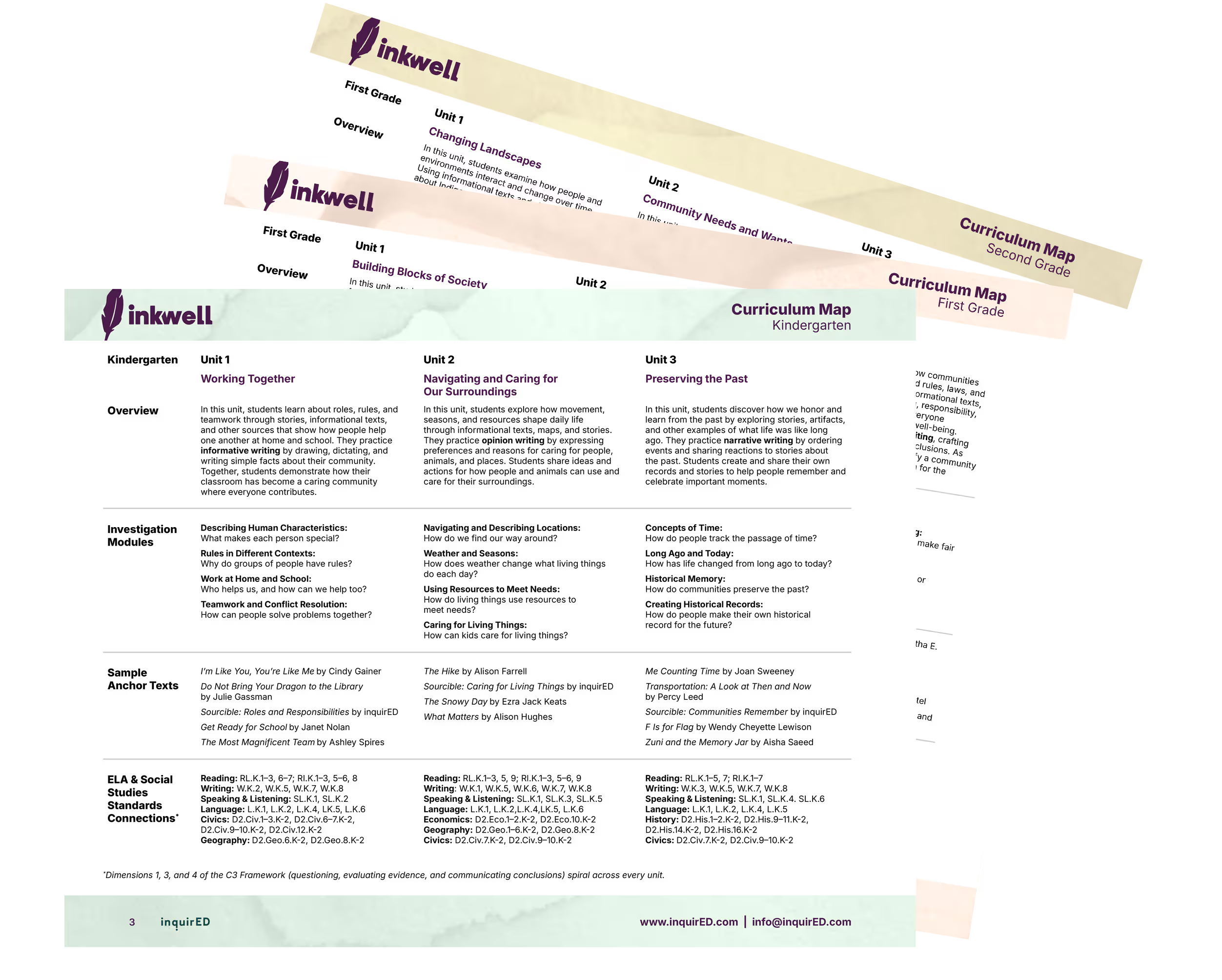

Inkwell K–2 Curriculum Map

Get a first look at how our K–2 curriculum integrates core ELA and core social studies into one instructional block.

Start your journey

Inquiry Journeys, inquirED's K-5 social studies curriculum, engages students in inquiry-based learning, strengthens literacy skills, and supports teachers every step of the way.

inquirED supports teachers with high-quality instructional materials that make joyful, rigorous, and transferable learning possible for every student. Inkwell, our integrated core ELA and social studies elementary curriculum, brings ELA and social studies together into one coherent instructional block that builds deeper knowledge, comprehension, and literacy skills. Inquiry Journeys, our K–5 social studies curriculum, is used across the country to help students develop the deep content knowledge and inquiry skills essential for a thriving democracy,